DEF CON Quantum CTF 2024: Walkthrough

I had the chance to participate in the DEF CON 32, with the purpose to expand my knowledge about hacking domains that are less known or completely unknown to me. With the overwhelming possibilities proposed on very different topics by more than 30 villages, I tried to select the most interesting talks, workshops and activities to discover new subjects I did not know (much) about.

The first workshop on my list was an introduction to Q# in the Quantum village. Like most of the “classic computing” hackers, I have heard about quantum computing, featuring the qubits leveraging the quantum physics implemented in quantum computers, for which one of the interest would be to be able to break classic encryption in the future.

Q# is a language that allows us to simulate quantum computing, and this was a nice introduction to its key concepts, using the Azure Quantum katas. While I always saw quantum physics as bit of a mystery, because I never crossed the subject during my computer science studies, I was surprised of the logic behind. Basically, in quantum computing everything can be represented using complex arithmetic (imaginary numbers) and linear algebra (matrices). Because of the imaginary numbers, some intuitive concepts in classic computing are no more in quantum computing, such as read the value a qubit variable (depending on its state, you could end up in probabilistic results).

Just after the workshop, while I continued my exploration of the conference, I looked at the CTF organised by the Quantum village “QOLOSSUS”. I was expecting difficult and exotic challenges, that would target more physicians or mathematicians, a bit like the cryptography domain. This was true in a sense as I did not notice as much competition as we often see for other CTFs with web application hacking or so, but the challenges ranked from very beginner to more advanced ones. The CTF featured different categories, among them:

- Q#

- Quantum Key Distribution (QKD)

- OpenQASM (circuits)

Each of the categories presented an introduction challenge to get your feet wet, that would unlock all the category challenges once solved. By playing around, I noticed that I was able to solve some easy ones. Given that the majority of the winners of the previous editions of this CTF (this was the 3rd edition) never did quantum computing prior to the competition, and that I had the required mathematics background to understand the topic, I decided to take my chance in this competition, revamping my planned schedule for this DEF CON to dedicate most of my time around the Quantum village.

This effort paid off at the end. I was able to reach the 3rd place in the competition!

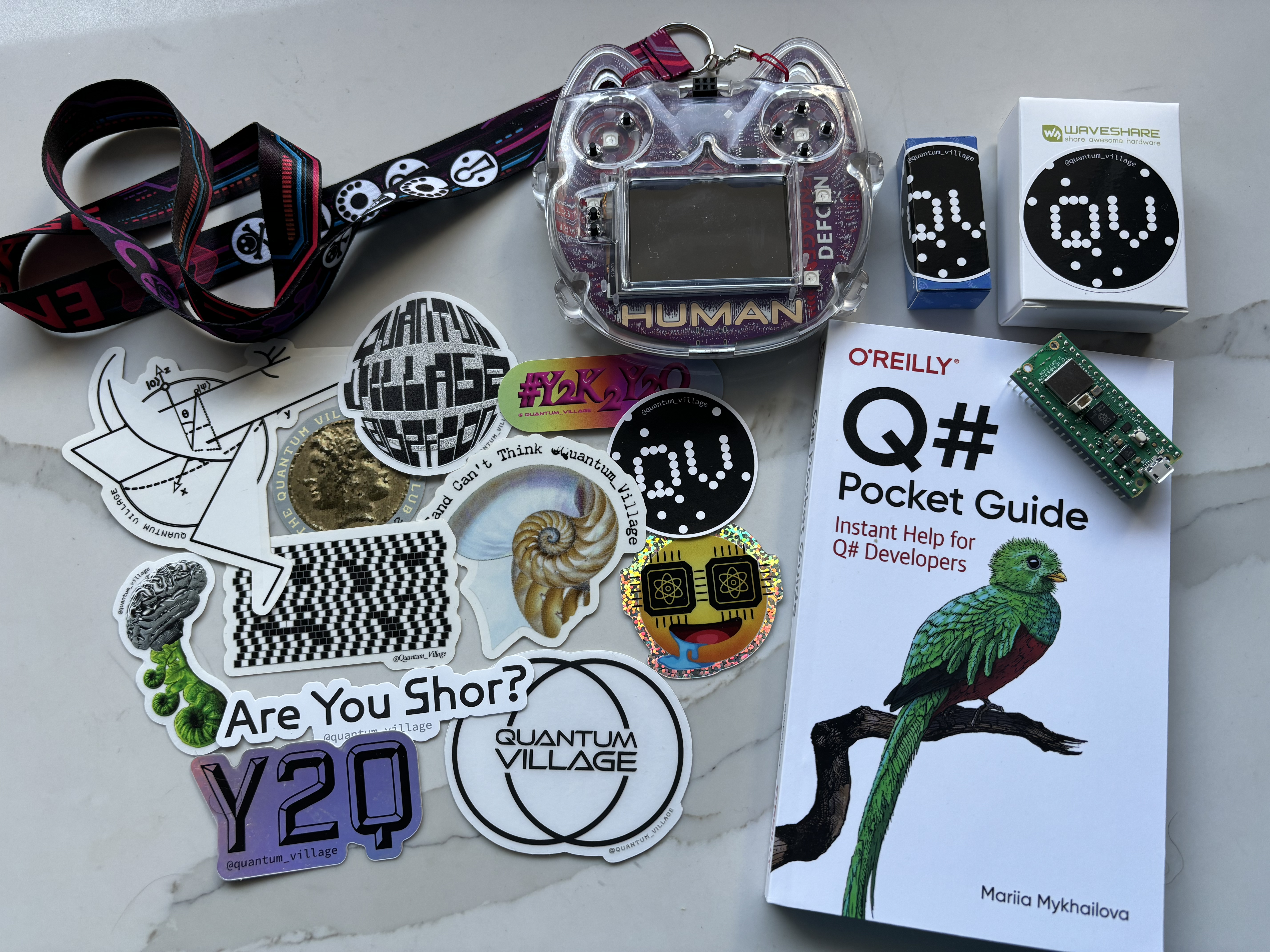

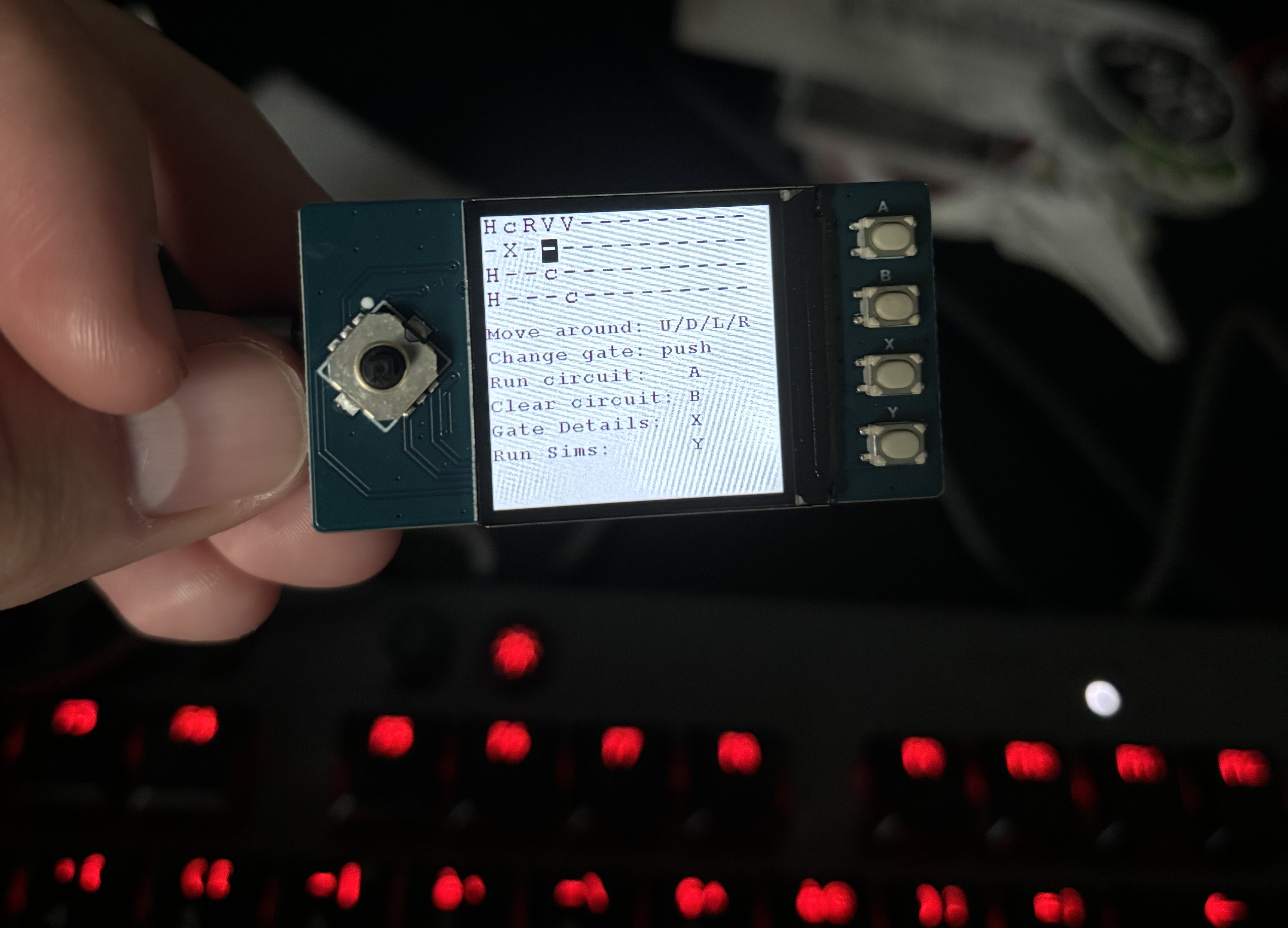

On top of my newly acquired knowledge on this emerging subject, I received some nice rewards like a dedicated book by Mariia Mykhailova, a small quantum emulator and real quantum computing time on Oxford Quantum Circuit’s Toshiko Gen-I!

This is an exciting new hacking domain, as it will grow and spread in the years and decades to come, being the new reference for secure communications or faster computing. I am very curious to witness what the hacking perspective will be on quantum computing in the future!

Below I walk trough the first challenge featured this year in the Q# category. I highly recommend the Azure Quantum katas as a free ressouce available to learn about quantum computing and Q#.

Q# challenge 1

Description

Write Q# code to figure out which of the two possible unitaries you are given. Inputs: 1) An operation that implements a single-qubit unitary transformation: either U₁ or U₋₁. 2) A qubit in state |ψ⟩ such that U₁|ψ⟩ = |ψ⟩ and U₋₁|ψ⟩ = -|ψ⟩. The operation will have Adjoint and Controlled variants defined. Output: 0 if the given operation is U₁, Output: 1 if the given operation is U₋₁. The state of the qubit at the end of the operation does not matter. Here is the code prototype to use:

operation DistinguishUOneUMinusOne(u : Qubit => Unit is Adj + Ctl, psi : Qubit) : Int {

//YOUR CODE HERE

return -1;

}

Walkthrough

The task is straightforward once we know the gates that transform our qubits, as well as fundamental fonctions in Q#.

The objective was to determine whether the given operation u was U₁ or U₋₁. The key to solving this problem lies in the specific properties of the qubit states under the unitaries U₁ and U₋₁. Here’s a breakdown of the situation:

- When U₁ is applied to the qubit ψ, the qubit remains in the state |ψ⟩.

- When U₋₁ is applied, the qubit’s state is inverted (multiplied by -1), resulting in - |ψ⟩.

We need to construct a quantum circuit that can distinguish between these two scenarios. We will use two very common elements in quantum computing to accomplish this: the Hadamard gate and a controlled operation.

Here are the steps we will implement:

- Preparing an auxiliary qubit in the |0⟩ state. This qubit will act as a control qubit in the controlled operation.

- Applying a Hadamard gate (H) to the auxiliary qubit to create a superposition: H(|0⟩) = ∣+⟩

- Applying the controlled version of the operation u to the target qubit ψ, with the auxiliary qubit as the control. This operation entangles the auxiliary qubit with the target qubit based on whether U₁ or U₋₁ is applied.

- Applying another Hadamard gate to the auxiliary qubit after the controlled operation helps to disentangle the auxiliary qubit from the target qubit, leaving the auxiliary qubit in a state that reflects whether U₁ or U₋₁ was applied.

I struggled a bit to understand how the steps 3 and 4 worked, because we need to understand how a controlled operation works for the step 3, and how it leverages quantum mechanics to distinguish the u operation. For the step 4, the Hadamard gate plays a crucial role in determining the outcome. Specifically, the second Hadamard gate effectively transforms the information encoded in the entanglement between the auxiliary and target qubits back into the computational basis. This method highlights the power of quantum entanglement and interference in extracting information about quantum operations.

How the controlled operation works?

When we apply the controlled operation Controlled u([aux], ψ);, the following happens:

If the Control Qubit is in State |0⟩

The operation u is not applied to the target qubit ψ. The target qubit remains unchanged.

If the Control Qubit is in State |1⟩

The operation u is applied to the target qubit ψ. Depending on whether u is U₁ or U₋₁, the state of the qubit ψ will either remain the same (if U₁) or flip its phase (if U₋₁).

Why can we distinguish U₁ from U₋₁?

This is where the power of quantum mechanics comes into play. Since the control qubit (aux) is in a superposition of |0⟩ and |1⟩, the controlled operation creates an entangled state between the control qubit and the target qubit. This entanglement reflects the effect of the unitary u on ψ based on whether u is U₁ or U₋₁.

Effect of U₁

If u is U₁, the state ψ remains unchanged regardless of whether the control qubit is |0⟩ or |1⟩. The overall state of the system (control + target) after the controlled operation is still in a form where the control qubit is not significantly affected when we later apply another Hadamard gate.

Effect of U₋₁

If u is U₋₁, applying u when the control qubit is |1⟩ flips the phase of ψ. This introduces a relative phase difference in the superposition of the control qubit, which is crucial because it alters the outcome of the next Hadamard operation on the control qubit.

Result of the second Hadamard gate

After applying the controlled operation, we apply another Hadamard gate to the auxiliary qubit. This second Hadamard gate disentangles the qubits and collapses the control qubit back to a definite state.

- If u was U₁: We have H(|+⟩) = |0⟩, leading to a measurement of 0.

- If u was U₋₁: We have a phase flip introduced to our auxiliary bit, resulting in H(|-⟩) = |1⟩, leading to a measurement of 1.

Note that before returning the result, for best practice, even though we know that our code will be executed in a simulator for this CTF, we want to ensure that the auxiliary qubit is restored to the |0⟩ state for future use.

Here is the complete Q# code to solve the challenge:

operation DistinguishUOneUMinusOne(u : Qubit => Unit is Adj + Ctl, psi : Qubit) : Int {

// Prepare an auxiliary qubit in the |0⟩ state

use aux = Qubit();

// Apply Hadamard gate to the auxiliary qubit to create a superposition

H(aux);

// Apply controlled-U operation

Controlled u([aux], psi);

// Apply the second Hadamard gate to the auxiliary qubit

H(aux);

// Measure the auxiliary qubit

let result = M(aux);

// Best practice: reset the auxiliary qubit

Reset(aux);

// Return 0 if the result is Zero, 1 if the result is One

return result == Zero ? 0 | 1;

}

Leave a comment